Are Cows Getting a Free Pass on Methane Emissions?

January 20, 2025 § Leave a comment

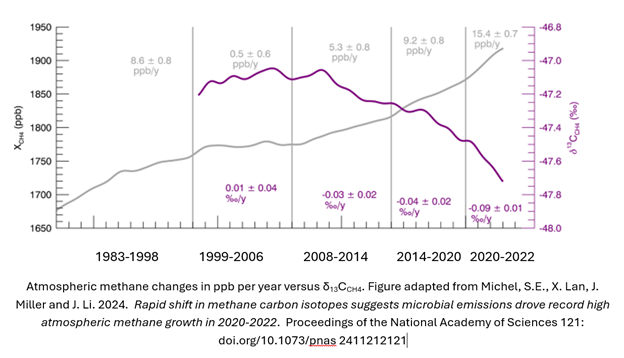

A recent study reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1 convincingly shows that atmospheric methane increases in the last 15 years can be attributed primarily to microbial sources. These comprise ruminants (cows in the main), landfills and wetlands. Yet, policy action on methane curbing has largely been focused on leakage in the natural gas infrastructure. In the US as well as in Canada, policies have fallen short of comprehensive action in the agricultural sector2,3.

Before we discuss the study, first some (hopefully not too nerdy) basics. Methane has the chemical formula CH4. The common variety designated 12CH4, has 6 protons and 6 neutrons in the nucleus. An isotope, 13CH4, has an additional neutron. The 13CH4 to 12CH4 ratio is used to detect the origin of the CH4. The actual ratio is compared to that of a marine carbonate, an established standard. The comparison is expressed as δ13CCH4 with units ‰ and is always a negative number because all known species have a lower figure than that of the standard carbonate. Microbially sourced methane will have ratios of approximately -90 ‰ to -55 ‰ and methane from natural gas will be in the range -55 ‰ to -35 ‰. This is the measure used to deduce the source of methane in the atmosphere.

Here is the lightly adapted main figure from the cited study. The data are primarily from The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, but as shown in the paper, similar results have been observed from other international sources. The gray line is the atmospheric methane, shown as increasing steadily over decades, but with steeper slopes in the near years. The steeper portion is roughly consistent with the period in which the isotopic ratio becomes increasingly negative. This implies more negative contribution, which in turn means that the main contributory species is microbial. Note also the increased severity of the trend in 2020-2022, and coincidentally or not, increased methane in atmosphere slope in those years. The paper authors do not see the correlation as coincidental. They emphatically state: our model still suggests the post-2020 CH4 growth is almost entirely driven by increased microbial emissions.

A quick segue into why methane matters. The global warming potential of methane is 84 times that of CO2 when measured over 20 years, and 28 times when measured over 100 years. Climatologists generally prefer to use the 100-year figure (and I used to as well), but urgency of action dictates that the 20-year figure be used. The reason for the difference is that methane breaks down gradually to CO2 and water, so it is more potent in the early years.

These research findings point to the need for policy to urgently address microbial methane production. This does not mean that we let up on preventing natural gas leakage, the means to do which are well understood. The costs are also well known and, in many cases, simply better practice achieves the result. In fact, the current shift to microbial methane being a relatively larger component could well be in response to actions being taken today to limit the other source. But it does mean that federal actions must target microbial sources more overtly than in the past. We will touch on a few of the areas and what may be done.

Landfill gas can be captured and treated. In the US, natural gas prices may be too low to profitably clean landfill methane sufficiently to be put on a pipeline. Part of the problem is that, due to impurities such as CO2, landfill methane has relatively low calorific value, almost always well short of the 1 million BTU per thousand cubic feet standard for pipelines. However, technologies such as that of M2X can “reform” this gas to synthesis gas, and thence to methanol, and a small amount of CO2 is even tolerated (Disclosure: I advise M2X).

Methane from ruminants (animals with four-compartment stomachs tailored to digest grassy materials) is a more difficult problem. Capture would be operationally difficult. The approach being followed by some is to add an ingredient to the feed to minimize methane production. Hoofprint Biome, a spinout from North Carolina State University, introduces a yeast probiotic to carry enzymes into the rumen to modify the microbial breakdown of the cellulose with minimal methane production. I would expect this more efficient animal to be healthier and more productive (milk or meat). Nailing down of these economic benefits could be key to scaling, especially for dairies, which are challenged to be profitable. Net-zero dairies could be in our future.

Early-stage technologies already exist to capture methane from the excrement from farm animals such as pigs. These too could take approaches similar to those proposed for landfill gas, although the chemistry would be somewhat different. Several startups are targeting hydrogen production from pyrolysis of methane to hydrogen and carbon. The latter has potentially significant value as carbon black, for various applications such as filler in tires, and biochar as an agricultural supplement. If the methane is from a source such as this, the hydrogen would be considered green in some jurisdictions.

The federal government ought to make it a priority to accelerate scaling of technologies that prevent release of microbial methane into the atmosphere. With early assists, many approaches ought to be profitable. Then it would be a bipartisan play*.

Vikram Rao

*Come together, right now, from Come Together, by The Beatles, 1969, written by Lennon-McCartney

1 Michel, S.E., X. Lan, J. Miller and J. Li. 2024. Rapid shift in methane carbon isotopes suggests microbial emissions drove record high atmospheric methane growth in 2020-2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121: doi.org/10.1073/pnas 2411212121

2 Patricia Fisher https://fordschool.umich.edu/sites/default/files/2022-04/NACP_Fisher_final.pdf

3 Ben Lilliston 2022 https://www.iatp.org/meeting-methane-pledge-us-can-do-more-agriculture

Leave a comment