Can Batteries Pivot from EVs to Grid Support?

February 21, 2026 § Leave a comment

The February 12 print edition of the NY Times had a piece under the Climate Forward banner on A2. It observes that policy actions have led to a decrease in demand for electric vehicles (EVs), and that at least two auto manufacturers are pivoting to repurposing battery manufacturing to supply the market for storage in support of two areas with relatively robust demand. These are electricity grids with intermittency in renewable power and data centers.

First, the premise. Certainly, policy measures by the government, especially the repeal of the tax credit, have reduced the consumer demand for EVs in the US. Equally, grids continue to add renewable capacity, in part due to demand and in part due to solar electricity today being the lowest-cost form of energy. However, due to low capacity factors, and temporal fluctuations, this source requires storage as backup. The most ubiquitous storage means are batteries.

The newest entrants into the power demand sweepstakes are data centers, as noted in the NYT piece. The owners of these power hogs prefer electricity that is substantially carbon free. Microsoft went so far as to enable de-mothballing of the Three Mile Island conventional nuclear plant and guaranteeing offtake at a heavy premium to prevailing prices in the region. Expect also more “behind the meter” capability, meaning not acquired from the grid. This business model is a net benefit to consumers in the region because the cost will not be passed on to them.

The pivot to repurpose EV batteries to grid support applications is informed by the fact that EV batteries have two distinct cathode chemistries, and one is more suited to the stationary application. For the same storage capacity, the Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC) variant is lighter, but more costly than the Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP). In the EV application the lightness often trumps the cost element primarily because longer range can be achieved with manageable addition to weight. Longer range and fast charging have emerged as dominating features sought by customers, especially in the higher end sedan and SUV lines. This has resulted in the vast majority of passenger EVs being powered by NMC batteries. In fact, to my knowledge, the only passenger EV using LFP batteries is the Tesla Model 3 with rear-wheel drive. This is a vehicle that targets the lower cost and limited range market segment. Pickup trucks are more suited to LFPs because they can generally tolerate the extra weight. The standard range Ford 150 Lightning uses LFPs and the extended range one uses NMCs.

To recap, defining characteristics of batteries in EV applications are high energy density and light weight, allowing for greater range before requiring recharging. By contrast, grid support batteries are not too bothered by these characteristics, because space is not at a premium, and the extra weight is tolerated in exchange for lower prices. But they prioritize the feature of longer life, defined by surviving more numerous charge/discharge cycles. This is because grid support requires batteries to be recharged much more frequently than in the motive application.

LFP batteries were invented by Prof. Goodenough at the University of Texas, Austin. He shared the Nobel Prize with two others in 2019 for lithium-based batteries as a class. While invented in the mid-1990s, LFPs were initially shunned by EV manufacturers. The defining characteristic of an LFP is the longer life. These batteries last for over 4 times as many charge/discharge cycles as NMC equivalents. All rechargeable battery lives benefit from not fully charging or discharging, and NMC batteries, including the ones in cell phones, last longer if charged just to the 80% level. LFP batteries are something of an exception in that a full charge to 100% has minimal impact on life. Another in the plus column for LFPs. A further plus is that LFP batteries are also believed to be safer.

The use of iron in place of more scarce imported cobalt, manganese and nickel is preferable from a resilience standpoint. Compared to the other metals, the price of iron is greatly lower and more stable. Cobalt has been particularly volatile, ranging from USD 22,000 to 94,000 per metric ton over the last eight years. Importantly, much of the volatility on the upside has been attributed to EV demand.

Now to the pivot. All EV batteries could, in principle, be used in the grid support market. But as noted above, LFPs are more suited, and their preferential use will likely stabilize the price of cobalt, thus benefiting the NMC market. Further, manufacturers of the LFP variant will have cost and desirability advantages in serving the grid market and, to a degree, in competing with Chinese imports. A NYTimes story on February 16 notes that the F15 Lightning battery plant in Tennessee is being shut down but may re-start to serve storage. They can manufacture both types but would be well served to make just LFPs. Absent tariffs, NMC batteries will have a tough time competing with imported LFPs.

In conclusion, the pivot makes more sense for the LFP* than for the NMC EV battery variant.

* The slow one now, will later be fast, from The Times They are a Changin’ (1964), written and performed by Bob Dylan

Vikram Rao

February 21, 2026

LNG’s Tax Break Controversy

August 5, 2025 § Leave a comment

A story is breaking that Cheniere Energy is applying retroactively for an alternative fuel tax credit for using “boil off” natural gas for propulsion of their liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers in the period 2018 to 2024, the year that tax break expired. The story leans towards discrediting the merits of the application. Before we get into that, first some basics.

LNG is natural gas in the liquid state. In this state it occupies a volume 600 times smaller than does free gas, thus making it more amenable to ocean transport. It achieves this state by being cooled down to – 162 degrees C. Importantly, it is kept cool not by conventional refrigeration, but by using the latent heat of evaporation of small quantities of the liquid. If the resultant gas is released to the atmosphere, it is a greenhouse gas 80 times more potent than CO2 over 20 years. In recent years, tanker engines have been repurposed to burn natural gas. The “boil off” gas, as it is referred to, is captured, stored and used for motive power. As with most involuntary methane release situations, capture has the dual value of economic use and environmental benefit. In the case of LNG tanker vessels, the burn-off can handle most of both legs of the voyage. Short haul LNG trucks also have boil off gas, and it is unlikely that the expense of recovery and dual fuel engines is incurred.

Also, by way of background, Cheniere Energy is a pioneer in LNG. It began with their construction of import terminals in the 2008 timeframe. Shortly after that US shale gas hit its stride and LNG imports evaporated. This was followed by US shale gas becoming a viable source of LNG export, and Cheniere again took the lead in pivoting to convert import terminals to export capability. Today they are the leading US exporters.

Now to the merits of considering boil off natural gas as an alternative fuel. The original intent of the law, which expired in 2024, appears to have been to encourage substitution of fuel such as diesel with a cleaner burning alternative. However, the letter of the law limits this to surface vehicles and motorboats. LNG vessels are powered by steam (using a fossil fuel or natural gas), and more lately by dual fuel engines using boil off gas and a liquid fuel ranging from fuel oil to diesel. Using a higher proportion of boil off gas certainly is environmentally favorable, mostly because sulfur compounds will essentially not be present and particulate matter will be vastly lower than with diesel or fuel oil. If this gas was not used for power, hypothetically, it would be flared, leading to CO2 emissions and possibly some unburnt hydrocarbons. Capture and reuse provide an economic benefit, so should it qualify as an alternative fuel?

An analog in oil and gas operations could be instructive. Shale oil can be expected to have associated natural gas because light oil tends to do that because of the mechanism of formation of these molecules. Heavy oil, for example, could be expected to have virtually no associated gas. When oil wells are in relatively small pockets and/or in remote locations and because of the relatively small volumes or remoteness, export pipelines are not economic. This gas is flared on location. Worldwide 150 billion cubic meters was flared in 2024, an all-time high. Companies such as M2X Energy capture this and convert it to useful fuel such as methanol, and in the case of M2X the process equipment is mobile. The methanol thus produced could be considered green because emissions of CO2 and unburnt alkanes would be eliminated.

Were that to be the case, the use of boil off gas has some legs in consideration of it being an alternative fuel. However, the key difference in the analogy is that in the case of the LNG vessel, an economic ready use exists. Not so in the remotely located flared gas. But is an economic ready use a bar for consideration? Take the example of CNG or LNG replacing diesel in trucks. They likely quality for the credit. The tax break approval may well come down to a hair split on the definition of motorboat. An LNG vessel is certainly a boat, and has a motor, but does not neatly classify as a motorboat in the parlance*. But if the sense of the law is met, ought the letter of the law prevail?

Vikram Rao

*That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet, Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, Act II, Scene II (1597), written by W. Shakespeare.

The Frac’ing Dividend

June 29, 2025 § Leave a comment

Few will dispute the fact that the US was a net importer of natural gas in 2007. Cheniere Energy was gearing up to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) and deliver it to the country. Then natural gas from shale deposits became economic and scalable. How Cheniere reinvented their business model by pivoting to convert their re-gas terminals to become LNG producers is a story for another time. As is the tale of shale gas singlehandedly lifting the US out of recession. Low-cost energy is a tide that lifts all boats of economic prosperity, and this one sure did.

The story for today is that the technologies that enabled shale gas production are showing up as key enablers for geothermal energy, the leading carbon- free energy source which can operate 24/7/365, unlike solar and wind, which are intermittent, with capacity factors (roughly defined as the portion of time spent delivering electricity) of up to 25% and 40%, respectively. The short duration intermittency (frequently defined as under 10 hours) is covered by batteries. But for longer periods, the most promising gap fillers are geothermal energy, small modular (nuclear) reactors and innovative storage means. Of these, the furthest along are geothermal, as represented by advanced geothermal systems (AGS), some battery systems, and hydrogen from electrolysis of water using power when not needed by the grid.

The most commercially advanced AGS variant is that of Fervo Energy. It employs two parallel horizontal wells intended to be in fluid communication. Hydraulic pressure is used to create and propagate fractures from the injector well towards the induced fractures at the producer well. Fluid is pumped into the injector well and flows through the fracture network into the producer well. Along the way, it heats up while traversing hot rock. This hot fluid is used to generate electricity. It may also be used for district or industrial heating. The heat in the rock is replenished by heat transfer from near the center of the earth, where it is created by the decay of radioactive substances. The center of the earth is at temperatures close to that of the sun.

The two key enabling technologies for accomplishing the process described above are those of horizontal drilling (and drilling a pair reasonably parallel to each other) and hydraulic fracturing, known in industrial parlance as “frac’ing”. Clever modeling (from a co-founder’s PhD thesis at Stanford) dictates many operational parameters such as optimal well separation, but the guts of the operation is that employed in shale oil and gas production. With one difference. The temperatures are greater than in most conventional shale operations. This affects the drilling portion more than the fracturing one. Temperatures will be greater than 180 C in AGS operations, and in excess of 350 C in the so-called closed loop systems (which have no fracturing involved, except for one minor variant). Even in AGS systems, higher temperatures are preferred, and Fervo recently demonstrated operations at 250 C. While this stresses industry capability, it still falls firmly in oil and gas competency and the geothermal industry can rely upon this rather than attempt to invent in that space.

The frac’ing dividend mentioned in the title of this piece refers to advances in frac’ing operations which accrue directly to the benefit of AGS operations. A key one is the ability to use “slick water”, which is fracturing fluid with little to no chemicals. Opponents of shale gas operations have often cited the possibility of surface release of these chemicals as a concern. Similarly, accidental surface release of hydrocarbons in fracturing fluid has been a concern but is irrelevant here because of the complete absence of hydrocarbons in the rock being drilled. AGS operations do have the possibility of induced seismicity. This is where the pressure wave from the hydraulic pressure potentially energizes an active fault, if present in proximity, and the resulting slip (movement between rock segments) causes a sound wave in the seismic range. However, the risk is small, especially if the activity is in a naturally fractured zone, in which fractures can be propagated at lower induced pressures than in unfractured rock. In any event, competent operators such as Fervo are placing observation wells and to date induced seismicity has not been a concern. The sound heard is that of (relative) silence*.

Finally, the shale oil and gas industry devised economies of scale by placing multiple wells on each “pad”. These techniques, including elements such as the rigs moving swiftly on rails, are directly applicable to AGS systems using frac’ing. So, any reported economics of single well pairs could, in my opinion, be improved by up to 40% when tens of well pairs are executed on a single pad.

This is the big frac’ing dividend.

Vikram Rao

June 29, 2025

*And no one dared disturb the sound of silence, from The Sound of Silence, performed by Simon and Garfunkel, 1965, written by Paul Simon.

Are Cows Getting a Free Pass on Methane Emissions?

January 20, 2025 § Leave a comment

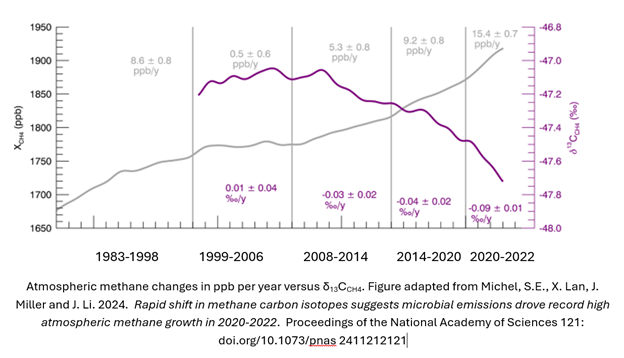

A recent study reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1 convincingly shows that atmospheric methane increases in the last 15 years can be attributed primarily to microbial sources. These comprise ruminants (cows in the main), landfills and wetlands. Yet, policy action on methane curbing has largely been focused on leakage in the natural gas infrastructure. In the US as well as in Canada, policies have fallen short of comprehensive action in the agricultural sector2,3.

Before we discuss the study, first some (hopefully not too nerdy) basics. Methane has the chemical formula CH4. The common variety designated 12CH4, has 6 protons and 6 neutrons in the nucleus. An isotope, 13CH4, has an additional neutron. The 13CH4 to 12CH4 ratio is used to detect the origin of the CH4. The actual ratio is compared to that of a marine carbonate, an established standard. The comparison is expressed as δ13CCH4 with units ‰ and is always a negative number because all known species have a lower figure than that of the standard carbonate. Microbially sourced methane will have ratios of approximately -90 ‰ to -55 ‰ and methane from natural gas will be in the range -55 ‰ to -35 ‰. This is the measure used to deduce the source of methane in the atmosphere.

Here is the lightly adapted main figure from the cited study. The data are primarily from The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, but as shown in the paper, similar results have been observed from other international sources. The gray line is the atmospheric methane, shown as increasing steadily over decades, but with steeper slopes in the near years. The steeper portion is roughly consistent with the period in which the isotopic ratio becomes increasingly negative. This implies more negative contribution, which in turn means that the main contributory species is microbial. Note also the increased severity of the trend in 2020-2022, and coincidentally or not, increased methane in atmosphere slope in those years. The paper authors do not see the correlation as coincidental. They emphatically state: our model still suggests the post-2020 CH4 growth is almost entirely driven by increased microbial emissions.

A quick segue into why methane matters. The global warming potential of methane is 84 times that of CO2 when measured over 20 years, and 28 times when measured over 100 years. Climatologists generally prefer to use the 100-year figure (and I used to as well), but urgency of action dictates that the 20-year figure be used. The reason for the difference is that methane breaks down gradually to CO2 and water, so it is more potent in the early years.

These research findings point to the need for policy to urgently address microbial methane production. This does not mean that we let up on preventing natural gas leakage, the means to do which are well understood. The costs are also well known and, in many cases, simply better practice achieves the result. In fact, the current shift to microbial methane being a relatively larger component could well be in response to actions being taken today to limit the other source. But it does mean that federal actions must target microbial sources more overtly than in the past. We will touch on a few of the areas and what may be done.

Landfill gas can be captured and treated. In the US, natural gas prices may be too low to profitably clean landfill methane sufficiently to be put on a pipeline. Part of the problem is that, due to impurities such as CO2, landfill methane has relatively low calorific value, almost always well short of the 1 million BTU per thousand cubic feet standard for pipelines. However, technologies such as that of M2X can “reform” this gas to synthesis gas, and thence to methanol, and a small amount of CO2 is even tolerated (Disclosure: I advise M2X).

Methane from ruminants (animals with four-compartment stomachs tailored to digest grassy materials) is a more difficult problem. Capture would be operationally difficult. The approach being followed by some is to add an ingredient to the feed to minimize methane production. Hoofprint Biome, a spinout from North Carolina State University, introduces a yeast probiotic to carry enzymes into the rumen to modify the microbial breakdown of the cellulose with minimal methane production. I would expect this more efficient animal to be healthier and more productive (milk or meat). Nailing down of these economic benefits could be key to scaling, especially for dairies, which are challenged to be profitable. Net-zero dairies could be in our future.

Early-stage technologies already exist to capture methane from the excrement from farm animals such as pigs. These too could take approaches similar to those proposed for landfill gas, although the chemistry would be somewhat different. Several startups are targeting hydrogen production from pyrolysis of methane to hydrogen and carbon. The latter has potentially significant value as carbon black, for various applications such as filler in tires, and biochar as an agricultural supplement. If the methane is from a source such as this, the hydrogen would be considered green in some jurisdictions.

The federal government ought to make it a priority to accelerate scaling of technologies that prevent release of microbial methane into the atmosphere. With early assists, many approaches ought to be profitable. Then it would be a bipartisan play*.

Vikram Rao

*Come together, right now, from Come Together, by The Beatles, 1969, written by Lennon-McCartney

1 Michel, S.E., X. Lan, J. Miller and J. Li. 2024. Rapid shift in methane carbon isotopes suggests microbial emissions drove record high atmospheric methane growth in 2020-2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121: doi.org/10.1073/pnas 2411212121

2 Patricia Fisher https://fordschool.umich.edu/sites/default/files/2022-04/NACP_Fisher_final.pdf

3 Ben Lilliston 2022 https://www.iatp.org/meeting-methane-pledge-us-can-do-more-agriculture

Drill Baby Drill, Drill Hot Rocks

December 5, 2024 § Leave a comment

“Drill baby drill” is being bandied around, especially post-election, reflecting the views of the president-elect. Thing is, though, baby’s already been drilling up a storm. World oil consumption was at an all-time high in 2023, breaking the 100 million barrel per day (MMbpd) barrier. And the International Energy Association (IEA) projects further demand growth, to about 106 MM bpd by 2028. The IEA also projects the US as the largest contributor to the supply, provided the sanctions on Russia and Iran continue.

Courtesy the International Energy Association

To execute the stated intent to stimulate US production, all that the new White House needs to do is not mess with the sanctions. For ideological reasons they may be tempted to open the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge to leases. But none of the majors will come, and not even the larger independents. Easier pickings in shale oil and in wondrous new opportunities such as in Guyana. Is it still a party if nobody comes?

Note in the figure above that the projection by the IEA has roughly the same slope as the pre-pandemic period, with a bit of a dip in the out years ascribed to electric vehicles. And if that were not enough, world coal consumption hit a historic annual high of 8.7 billion tonnes in 2023, despite Britain, which invented the use of coal, closing its last mine this year. The largest increases were in Indonesia, India and China, in that order. Let me underline, both oil and coal hit all-time highs in usage last year. So much for the great energy transition.

So, what gives? China and India, two with the greatest uptick in coal usage, need energy for economic uplift, and for now that means coal for them, since they are net importers of oil and gas. Consider though that the same countries are numbers 1 and 3 in rate of adoption of solar energy. What this means is that solar and wind cannot scale fast enough to keep up with the demand. Making matters worse is the ever-increasing demand created by data centers.

One reason for not keeping up with demand is land mass required. Numbers vary by conditions, especially for wind, but solar energy needs about 5 acres per MW, while wind on flat land typically needs about 30 acres per MW. Compare that to a coal generating plant, which is 0.7 acres per MW (without carbon capture). Wind also tends to be far from populated areas, so transmission lines are needed, and much wind energy is curtailed due to those not being readily constructed. To add to the complication, both solar and wind plants have low capacity factors, under 40%. So, nameplate capacity is not achieved continuously, and augmentation is needed with batteries or other storage means. Finally, governments would like the communities with retired coal plants to benefit from the replacements. This is hard at many levels, not the least being availability of land mass, and because the land area required is many times that which was occupied by the coal plant being replaced. All this holds back scale.

Geothermal Energy. Two types of firm (high capacity factors) carbon-free energy that fit the bill in terms of land mass, are geothermal energy and small modular reactors. Here we will discuss just the former, which involves drilling wells into hot rock, pumping water in and recovering the hot fluid to drive turbines. Fervo Energy, in my opinion the leading enhanced geothermal (EGS) company (disclosure: I advise Fervo, and anything disclosed here is public information or my conjecture), has been approved for a 2 GW plant in Utah, which has a surface footprint of 633 acres. This calculates to about 0.3 acres per MW. The footprint of Sage Geosystems is also similar. Sage also has an innovative variant which takes advantage of the poroelasticity in rock, and which could provide load following backup storage for intermittency in solar and wind, thus enabling scale in a different way.

Aside from the favorable footprint of Fervo emplacements (incidentally, the underground footprint is significant because each of the over 300 wells is about a mile long), the technology is highly scalable for the following reasons. All unit operations are performed by oilfield personnel with no additional training, and therefore, readily available. Certainly, the technology is underpinned by unique modeling (developed in large part in the Stanford PhD thesis of a founder), but the key is that when oil and gas production eventually diminishes, the same personnel can be used here. In fact, an oil and gas company could have geothermal assets in addition to their oil and gas ones, and simply mix and match personnel as dictated by demand.

The shale oil and gas industry found that when multiple wells were operated on “pads”, cost per well came down significantly. Those learnings would apply directly to EGS. Accordingly, I would expect EGS systems at scale to deliver carbon free power, 24/7/365, at very favorable costs.

Governments and investors ought to take note that EGS variants are possibly the fastest means for economically displacing coal, and eventually oil. In the case of the latter, even that displacement does not eliminate jobs.

As the title revealed, the refrain now changes a bit to: Drill baby drill, drill hot rocks*.

Vikram Rao

* Lookin’ for some hot stuff, baby, in Hot Stuff by Donna Summer, 1979, Casablanca Records